The questions of epistemology have always interested me. What does it mean to know something? What is this whole knowledge thing anyways? Does it even matter? I have taken more philosophy classes than a normal human should and epistemology is the class that really stuck with me. It’s abstract, bizarre, and sometimes a load of BS. But it also makes you think critically about how we view the world and examine what we truly know.

So for you none philosophers out there, I wanted to present a brief history of epistemology. It shouldn’t be too hard to understand and then you can wow all of your friends with your knowledge (maybe?!). Disclaimer: Friends may not actually be wowed and may instead ridicule you.

A Brief History of Epistemology

Okay, so, what is knowledge? Philosophers for centuries have been trying to define what exactly knowledge is. Here is where it all began.

Knowledge = True Belief

To know something, you have to believe it, obviously. If you don’t believe that the sky is blue, you certainly don’t know that the sky is blue. Furthermore, the belief has to be true. If you believe the sky is red, the belief is false. Again, you know nothing (Jon Snow).

Let’s say you believe the sky is blue. That is a true belief. Do you know the sky is blue? Well, that gets tricky really fast. Maybe the sky isn’t blue, that is just how you perceive it. Maybe you’ve never seen the sky and only read about it in a book. Does that mean you know it?

We come to find that there is something more to knowledge than it simply being a true belief. Think of it this way: There is a person, we’ll call him Fool, who believes everything he is told. You walk up to Fool and say, “Hey Fool. Just wanted to mention that pigs can fly and the sky is blue. Also your name is indicative of a point someone is trying to make.” Would Fool know that the sky is blue? He believes it just as strongly as pigs flying. I think most people would think that Fool doesn’t know anything. He just believes things that happen to be true on occasion. That isn’t knowledge.

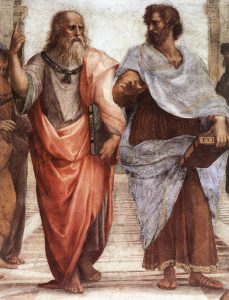

We see then that we need something else beyond a true belief. A little extra oomph. This was understood as far back as Plato. To solve this problem, we get something like:

Knowledge = Justified True Belief

This equation basically says that not only does the belief have to be true, but you need some justifiable reason to believe it. If you just randomly believe something, you don’t truly know it. But let’s say every time you have seen the sky, it has been blue. Everyone else seems to think it is blue too. And even scientists can explain that light refracting through the atmosphere makes the sky appear blue. Well, in that case, it seems pretty justifiable to believe it, so you can say you know that the sky is blue.

So there you have it. We defined knowledge and solved epistemology!

Then, in 1963, this guy called Edmund Gettier came along and ruined EVERYTHING.

Gettier argued that you can meet the justified true belief requirements but still not have knowledge. He laid out a couple examples himself, but my favorite Gettier-type example involves, of all things, barns.

Gettier Barns

Let’s say you are taking a drive through a shockingly barn-heavy town. I mean, these barns are everywhere. Hundreds of friggin’ barns. Each barn you pass looks like a barn, justifiably so. No reason to believe they aren’t barns. You drive through this whole town and believe them all to be barns.

Turns out, this barn town is even weirder, because not only does it have a ton of barns, it also has a bunch of barn facades. See, the townspeople loved barns so much, they built barn facades identical to real barns. Driving by, you would never know the difference.

Now, all up in your head, you have a bunch of justified beliefs. The facades, which you believe to be real barns, certainly isn’t knowledge (it’s a false belief). But what about the real barns? You had a justified reason to believe they were barns, but do you know they are barns? If you truly knew which barns were real, you could go back and point them out. But you can’t, because they are identical to the facades. At the end of the day, you don’t know which barns are real and which are facades, despite having a justified true belief.

The argument says just because you stumble upon a justified true belief, it doesn’t mean you truly know it. So what does this mean for our definition of knowledge?

Responses typically fall into three categories:

- The “Nuh-uh!” response. These people argue that Gettier examples don’t provide real justification. Knowledge = Justified True Belief is correct, we just need to figure out how to properly define this whole justification thing.

- The “Oh shit…” response. This group recognizes Gettier’s examples as a true problem and believe there is a fourth variable needed to define knowledge. You still need a justified true belief, but there is yet another factor involved.

- The “Blow it all up!” response. Recognizing that Gettier’s examples as valid, they reject that justification is needed. Instead, there is something else outside of justification in the knowledge equation.

Which leads us to a whole mess of philosophers trying to respond to Gettier. It is here where you might ask, “What’s the point?” I mean, why are we talking about knowledge equations when it seems we all know what knowledge already is. Isn’t it subjective?

It’s not something that I can possibly answer, but I do question the route epistemology has taken. Is knowledge something we can define? Philosophers have based epistemological definitions on what we believe (uh oh) to be knowledge. We reject theories because they are not properly defining knowledge. But how would we know if it was proper or not if we didn’t already know what knowledge is? Maybe knowledge, as a concept, is a priori in nature. Obviously you aren’t born with knowledge, but we all seem to understand the concept. Yet we spend centuries focusing on a definition.

I think that the battle to define knowledge leaves a lot of interesting questions off the table. Not that philosophers haven’t asked them, but it seems the entire epistemological field is focused on definition versus answers.

Epistemology is a fascinating exercise in logic. How do we define a concept like knowledge that can be accepted by all? And is the exercise itself valuable? Do we even know anything? Like all things in philosophy, we are left with more questions than answers.

(I pulled much of this article from memory, but Wikipedia helped quite a bit. If you are looking for deeper understanding, check out their good articles on Epistemology and the Gettier problem.)